When you're shaping metal, malleability tells you whether a part will form smoothly or crack under pressure. Some metals bend, stamp, roll, or press without trouble, while others fail as soon as you push them.

In this article, we break down what malleability is, why it matters in manufacturing, which industries rely on it most, and how it can help you choose the right material for your next project.

What is malleability?

Malleability is the measure of how easily a material can be compressed, flattened, or shaped without cracking. While ductility measures how a material stretches when pulled, malleability focuses on how it behaves under compressive forces, like hammering, rolling, or pressing.

If you picture a blacksmith hammering hot metal into thin shapes, that’s malleability in action. The more malleable the material, the more it can be reshaped without failure. Highly malleable metals form smooth surfaces and thin sheets, while less malleable ones fracture or crumble when heavily deformed.

Malleability mainly applies to metals, whereas plastics are usually evaluated with properties like ductility, toughness, or flexibility instead of compressive formability.

Malleability vs. other measurements

Malleability sits alongside other mechanical properties that help engineers predict how a metal will behave. If you want to explore how these properties interact, check out our full materials library and our manufacturing materials overview.

-

Malleability vs. ductility: Malleability is how much a metal can be shaped under compression. Ductility is how much it can stretch before breaking.

-

Malleability vs. hardness: Softer metals usually reshape more easily. Harder metals resist forming and can crack during bending.

-

Malleability vs. toughness: Toughness measures how much energy a material can take before breaking, which is different from how far it can be formed.

-

Malleability vs. yield strength: Yield strength tells you when permanent deformation starts. Malleability tells you how far that deformation can go before failure.

For a deeper look at how materials behave under tension, compression, and strain, see our guide to understanding material stress and strain.

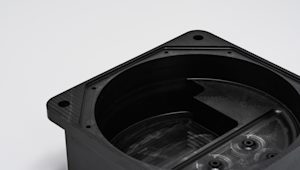

Why malleability matters in manufacturing

Forming processes—such as stamping, forging, rolling, and deep drawing—depend on how well a material can hold up to compressive deformation. This matters most in sheet metal fabrication, where materials need to bend and draw cleanly. In CNC machining, malleability only really matters if the part will be formed afterward. For metal 3D printing, malleability doesn’t affect the printing step itself, but heat treatments like stress relief or hot isostatic pressing (HIP) can make printed parts easier to shape without cracking. Plastics, whether in polymer 3D printing or injection molding, are rarely described by malleability, since they’re formed in their molten state and described by ductility, toughness, or melt behavior instead.

Choosing a malleable material gives you a few important advantages:

-

Reduced risk of cracking: Malleable materials tolerate local thinning and stress concentrations.

-

More complex shapes: Higher malleability enables deeper draws, tighter bends, and more uniform surfaces.

-

Lower forming forces: Materials that flow easily under compression reduce tool wear and energy consumption.

-

Better surface finish: Metals with higher malleability tend to distribute deformation evenly, avoiding tearing and surface defects.

How malleability is measured

Engineers measure malleability by compressing or bending samples until they fail.

-

Compression and flattening tests: Engineers compress a small cylinder or cube until it shortens or flattens. The more it can deform before cracking, the more malleable it is.

-

Bend tests: These check how far a material can bend without the surface starting to split. This is especially useful for sheet‑metal work.

-

Percent reduction: Engineers often look at how much a material can be compressed before failure. For example, going from 10 mm tall to 5 mm before cracking means a 50% reduction.

-

Hardness as a proxy: Hardness is often used as a rough proxy for malleability because softer metals, like gold, tend to deform more readily than harder ones, like steel. But the correlation isn’t perfect—microstructure, alloying, and heat treatment can make a metal soft yet still prone to cracking during forming.

Factors that affect malleability

Several variables influence how well a material can be shaped under compressive loads.

-

Crystal structure: Face‑centered cubic metals (aluminum, copper, gold, silver) form easily. Body-centered cubic metals (low-carbon steel) and hexagonal close-packed metals (magnesium, zinc, titanium) have fewer slip systems and typically form less smoothly.

-

Temperature: Warm metals form better while cold metals stiffen or become brittle.

-

Strain rate: Slow forming usually produces cleaner results than fast forming.

-

Impurities & grain size: Fine, even grains help a metal form smoothly. Some alloying elements (like carbon in steel or zinc in copper) increase strength but make forming harder.

Comparing malleability across materials

Here’s where common engineering metals sit on the malleability spectrum. These ranges help engineers choose the right balance of strength, formability, and final performance.

| Malleability level | Material | Crystal structure | Hardness (HV) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Bulk modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very high | Gold | FCC | 25 | 120 | 180 |

| Silver | FCC | 25–30 | 170 | 100 | |

| High | Copper C110 | FCC | 40–50 | 220 | 140 |

| Aluminum 6061 | FCC | 95 | 310 | 76 | |

| Moderate | Aluminum 7075 | FCC | 150 | 570 | 76 |

| Brass | FCC | 60–100 | 340 | 120 | |

| Stainless steel 304 | FCC | 170 | 515 | 160 | |

| Low-carbon steel | BCC | 120 | 370 | 160 | |

| Low | Titanium Grade 2 | HCP | 200 | 345 | 107 |

| Titanium Grade 5 | HCP | 350 | 950 | 110 | |

| Nickel alloys | FCC | 150–300 | 450–1300 | 180 | |

| Magnesium | HCP | 40–60 | 230 | 45 | |

| Very low | Cast iron | Mixed | 150–300 | 200 (brittle) | 90 |

*All values are approximate and vary with alloy composition, processing, and heat treatment. They should be used as general guidelines, not as guaranteed material specifications.

How post‑processing affects malleability

Heat treatments significantly change how a metal responds to machining and forming. They can soften materials for easier bending and shaping, or harden them afterward for final strength.

-

Annealing: Heating and slow cooling soften the metal, relieve stress, and improve formability. Common for aluminum, copper, low‑carbon steels, and annealed tool steels like D2 and S7.

-

Hot working: Forming metal while it’s heated above its recrystallization temperature keeps it soft and reduces cracking.

-

Solution treatment & aging: Common for aluminum and titanium. Solution treatment softens the alloy for forming, while aging restores strength afterward.

Industries that rely on malleability

Several industries rely on malleability because clean, predictable forming reduces cracking, lowers scrap rates, and supports complex geometries during manufacturing.

-

Automotive: Body panels, brackets, and crumple-zone components rely on metals that can bend and stretch without cracking. Mild steel and aluminum are used because they form cleanly and absorb energy in a crash.

-

Aerospace: Lightweight alloys must form into thin structures and brackets without failure. Controlled malleability helps avoid cracking during precision fabrication.

-

Industrial machinery & heavy fabrication: Formed steel plates, guards, tanks, and structural assemblies need metals that can handle heavy bending and rolling without fracturing.

-

Consumer electronics: Thin aluminum and copper parts stamp well and hold tight tolerances for housings and internal frames.

Design tips for malleable metals

When you’re designing a part that needs to be bent, shaped, or pressed, a few simple guidelines can make the forming process go much more smoothly.

-

Use a generous bend radius: Tighter bends increase cracking risk.

-

Expect springback: Stronger metals rebound more while softer ones rebound less.

-

Watch for thinning: Deep draws stretch material so choose metals that can handle it.

-

Time heat treatment wisely: Many alloys form best when soft and strengthen later.

-

Balance forming vs. strength: High-strength alloys are often harder to shape.

-

Use lubrication: Reduces friction and helps prevent surface cracks.

-

Check grain direction: Sheet metals bend more smoothly across the grain.

Get a quote

Need a part that can handle heavy pressure without cracking? Upload your design and we'll give you instant pricing on a malleable, form-friendly metal for your project.

Frequently asked questions

What’s the difference between malleability and ductility?

Malleability is the measure of compressive deformation, such as flattening and shaping. Ductility measures stretching under tension.

Can heat treatment improve malleability?

Yes. Processes like annealing and solution treatment generally soften the material and make it easier to form.

Are all soft metals malleable?

Not necessarily. Many soft metals are malleable, but crystal structure, impurities, and temperature all influence how well a metal forms. Some soft alloys can actually crack if their grain structure is unstable or if they’re deformed too quickly.

Why do some materials crack during forming?

Cracking usually happens when the material can’t handle thinning or stress. Low malleability, high strain rates, or insufficient heat can all make a metal more prone to failure.

Can malleability be increased through processing?

Yes. Annealing, hot working, and solution treatment all help restore or increase malleability by reducing internal stresses and improving grain structure.